Connect with us

Published

3 years agoon

Even though Washington state is winding down on its drug war, police are still seizing homes and cash from low-level suspects.

Take Jun Cong Pan, for example. “I made many mistakes,” he said. “I did wrong things.”

Arriving from China with his parents in 2002, Pan got a job cutting marble countertops, learned construction skills and branched out into remodeling houses. Unfortunately, an accident resulted in Pan cutting a tendon in his right hand. Anxious, depressed and unable to work, he ran up debts at local casinos and nearly lost his wife and child in the process.

Salvation seemed to beckon when a friend told Pan that growing cannabis was a good way to make money. The promise of steady, substantial income draws many who are struggling to make ends meet into greener indoor pastures.

However, Pan grew more cannabis than allowed by the license he had under Washington’s old medical marijuana system. He continued growing it after the license expired and sold it to the black market that continues to thrive outside the state’s heavily taxed legal cannabis regime.

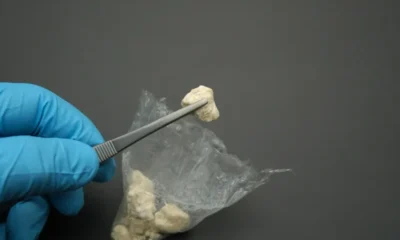

In November 2017, Seattle police raided Pan’s Skyway home and another house that he and his wife had owned but recently signed over to her parents. According to charging documents, police found 16 lights, grow gear, 84 freshly-cut plant stubs, and two bags of “shake” trimmings in the basement of the first house, as well as more than $20,000 in cash. In the second house, they found a much larger operation with 57 lights, 459 plants, and the cut plants from the first house hidden in Hefty bags tossed into the bushes.

More than three years later, Pan’s criminal case was wrapped up, and he got off lightly by pleading to a misdemeanor drug charge, a $500 fine, and serving five days on a work crew.

Unfortunately, this was just the beginning of his troubles.

The city of Seattle filed a lawsuit not against Pan, but against his houses, cars, family savings, and other property under an esoteric legal mechanism called “civil asset forfeiture.” This is something that Pan, and most Washington residents, never give thought to. The city claims that a “substantial nexus” exists between his property and crime. That they were used to produce marijuana or acquired with proceeds from that crime.

“They want to take our house, our car, our money,” Pan said. “I do one wrong thing, and this touches everyone in our family.”

Asset forfeiture is increasingly employed as an adjunct or, in some cases, alternative to criminal prosecution, especially in drug cases. It enables police departments in all but a few states to seize, keep, and sell property—from guns, cash, cars, and homes to lawn mowers and fishing lures – connected to a crime.

Washington’s forfeiture laws, among the most lax and opaque in the nation, grant police wide latitude in seizures with minimal oversight. Cities and countries in the state increasingly rely on forfeiture to underwrite policing, taking in $11.8 million statewide in 2019 and $11.9 million in 2020, more than in any other year since 2005.

Forfeiture actions rarely end up before a judge, but if they do, police need to only prove that it is more likely than not that the seized property was connected to a crime, a much lower bar than the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard required for a criminal conviction.

Critics of the practice argue that forfeiture is at best a distraction from public safety and at worst a scam, a threat to civil rights, and an open invitation to policing for profit.

According to Wesley Hottot, a litigator with the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public-interest law firm, police in several states have disproportionately targeted Black property owners for forfeiture. There are indications that Chinese and other Asian Americans are especially affected by forfeitures in Western Washington.

“Instead of doing this in wealthier communities around Detroit, where people will get lawyers, they do this in the inner city,” says Hottot, whose law firm sued to stop seizures there. “That tends to affect people in heavily policed communities and people of color.”

Douglas Hiatt, a Seattle defense attorney who has represented Pan and many other drug and forfeiture defendants, says civil forfeitures in Washington often target immigrants, especially Chinese immigrants.

“The thinking is, ‘as long as it doesn’t happen to a bunch of white people, we can do anything,” Hiatt said.

As in Pan’s case, police investigations of marijuana grow ops often follow complaints from neighbors. Hiatt contends those complaints are often “based in racist assumptions,” reflecting the political tenor of the times.

“People rat out their Asian neighbors,” Hiatt said. “I’ve heard one detective talk about people who are concerned about their property values going down when Chinese people move in.”

German Authorities to Ban Cannabis Smoking, Vaping at Festivals Including Oktoberfest

Ohio Company Signs Deal To Grow Hemp for Bioplastic

Gen Z Consumes Less Alcohol, Prefers More Cannabis and Non-Alcoholic Beverages

Colorado Senate Approves Legislation Banning Social Media Praise of Drugs

Study: CBD for Crack Use Disorder Comparable to Traditional Treatments, Less Side Effects

Snoop Dogg’s Dr. Bombay Ice Cream Launches New Flavor for 4/20